March 2, 2015 -- Naming our county after Isaac Shelby (1750-1826) might have been different. Actually, I have been unable to find any Isaac Shelby link to the state of Texas except for our county’s name. He was certainly a revolutionary war hero (an officer with the Virginia Minutemen) and consummate politician (twice governor of Kentucky), and he was also politically active in Virginia and North Carolina. At the time, his reputation must have spread from Kentucky and its bordering states, since today nine states (including Texas) have a county named after him.

March 2, 2015 -- Naming our county after Isaac Shelby (1750-1826) might have been different. Actually, I have been unable to find any Isaac Shelby link to the state of Texas except for our county’s name. He was certainly a revolutionary war hero (an officer with the Virginia Minutemen) and consummate politician (twice governor of Kentucky), and he was also politically active in Virginia and North Carolina. At the time, his reputation must have spread from Kentucky and its bordering states, since today nine states (including Texas) have a county named after him.

Without knowing for sure, perhaps there were a number of new Texans coming to the Tenehaw Municipality from the southeastern states in the early 19th century who thought of Isaac Shelby as their Revolutionary War hero and wanted a significant way to honor him. Nevertheless, there seem to be other choices of names for our county that reflect our history and that would have been more meaningful. Three men with direct ties to Shelby County during its formative period stand out in that regard.

Martin Parmer

Martin Parmer (1778-1850), legislator, judge, and signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, lived in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, and Arkansas before moving to Texas. In 1826 he joined Haden Edwards and fought for Benjamin Edwards in the Fredonian Rebellion. After he fled to Louisiana because of the collapse of the Rebellion, he returned to East Texas in 1835 and was elected as a delegate from the Tenehaw District (now Shelby County) to the Consultation of 1835. The following year San Augustine County sent him as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

Jonas Harrison

Before coming to Texas, Jonas Harrison lived in New Jersey and then moved to New York. He later practiced law in Detroit before moving south to Georgia. He and his new bride from Georgia subsequently traveled by horseback to northeastern Texas about 1820 and then moved to Shelby County. He lived on a farm near Patroon until his death in 1836. Actually, his contributions during his residency in Shelby County would gain for him a notable place in Texas history.

Jonas gave up his law practice for a time and worked his farm until 1826, when he decided to renew his practice in the newly-organized court system of Texas under Mexico (with offices in San Augustine and Shelbyville). This was a time when his talents were most urgently needed, since the entire area from Nacogdoches to the Sabine River was governed mainly by local officials, using guidelines established by Mexican authorities. He proved to be a most brilliant lawyer and would soon be recognized as one of the ablest statesmen ever to come out of East Texas.

In 1832 Jonas Harrison faced his first major challenge as a statesman. It was during a state-wide meeting convened to discuss how Texas might become more organized and independent while still working within the confines of the Mexican Government. Along with William English, Frederick Foye, George Butler, and John M. Bradley, Jonas Harrison represented the rather-new Tenehaw District at this convention.

The specific challenge faced by Jonas was as chairman of a major committee on land matters. He and his committee dealt with the question of Anglo settlers who had made substantial improvements to their farms, mills, cotton gins, and machinery, all in keeping with Mexican regulations but still without proper proof of ownership. It was perhaps the single most pressing issue that, when left unresolved, would ultimately lead to the Texas Revolution.

Jonas Harrison may best be remembered, however, for his presentation in 1835 at the first of three Constitutional Convention meetings. (The last two were in early 1836, with the Revolution then concluding in April of that same year.) According to Crocket's “Two Centuries in East Texas," Jonas Harrison presented a declaration on the relations with Mexico, setting forth the necessity for the complete separation of Texas from that country. This was described as a "masterly document, unanimously adopted by the Convention, and one compared favorably with any of the great state papers of the Revolution."

Other than Governor Oran M. Roberts, who came on the scene a bit late to be considered as our county’s namesake (settling instead on naming rights for a county later formed in 1876 out of a portion Bexar County), I can think of no other resident of Shelby County with such major contributions to the shaping of Texas—that is, except for his neighbor and colleague, Emory Rains.

Emory Rains

Some sources report that Emory Rains came to Texas from Tennessee as early as 1817, although the Texas State Historical Association gives his date of arrival in Texas as 1826. It seems probable, however, that he was in Shelby County at least by 1821, when he married Marana, daughter of Jonathan Anderson of the Patroon area.

The confusion of the date of Texas arrival may be explained in that Emory Rains actually came to Texas as a scout for his family, arriving first in what is Lamar County and then moving to southeast Shelby County. Two of his brothers, Preston Presley and George Raleigh, would soon follow him and settle near the Buena Vista area. While they were not active in government as was Emory, Preston and George Rains nevertheless made a positive impact on the development of Shelby County. The Rainsville Community near Huber was named after them.

Like his colleague and neighbor, Jonas Harrison, Emory's talents were in the political arena. Unlike Jonas, however, Emory was a self-taught lawyer. Jonas probably helped him in that regard, since Emory lived near Jonas and looked to him as a model and teacher.

In 1836 Emory was chosen as a senate representative from Shelby County in the first congress of the Republic of Texas, a position which he held until 1840. In 1845 he was elected to the Constitutional Convention for the new State of Texas and contributed to the original draft of our state's Constitution. Six years later he again represented Shelby County, this time in the congress of the State of Texas.

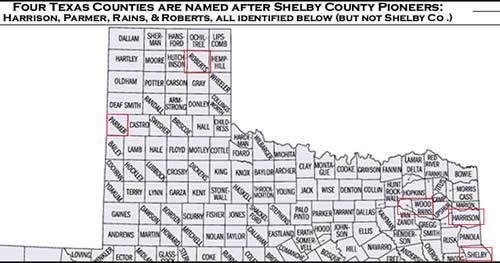

So, instead of Shelby, our county could have been named Parmer, Harrison, or Rains County. This, as you may know, is complicated by the fact that there are already counties in Texas with those three names. While Parmer County grew out of Bexar County in 1876, Harrison County was more of an after-thought, since the original county of Shelby in 1836 was divided to form other counties, including Harrison County in 1839 in the northern section of the original Shelby County.

Perhaps the evolution of Rains County is even more unusual.

Well after his contribution to the Republic of Texas and the new State of Texas as a representative of Shelby County, Emory moved to north-east Texas in mid-19th century and, among other contributions, surveyed the area that would soon be named Rains County. Then in 1866 he rode a mule to Austin for the purpose of getting a bill introduced to create Rains County. This, indeed, was accomplished in 1870; they even named their county seat after him (Emory).

It is with silent pride in our Shelby County forefathers when, on my way to Dallas on I-20, I pass Highway 19 north to Emory. And some day just maybe I’ll visit Rains County. I’m told there are some features of Emory that are reminiscent of Center.